Brazil’s financial services industry is facing a number of key changes, opening the door to fintechs with the advent of low-cost instant payments and Open Banking. Robin Arnfield reports

Brazil is characterised by heavy government, central bank regulation of payments, and the important role of fintechs and other new entrants in the banking and payments markets.

In 2018, the Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) established plans for a real-time 24/7 payments system that will be open to fintechs and payments institutions, and will facilitate mobile payment adoption. The new system will offer P2P, P2B, B2B and payments to and from government agencies, and will be operational by 2021.

Payments institutions are regulated by BCB, and are allowed to offer m-payment and m-banking services, including digital wallets, to low-income consumers. The BCB wants its instant payments system to be usable by all types of technology and through all kinds of institution. This opens the door to instant payments via QR codes, and between accounts held at card issuers and fintechs.

Brazil’s existing interbank payment systems only offer near-real-time transfers between bank accounts. They require considerable data input by payers and payees, and are only available during banking hours. They also have high fees – ranging from BRL2.30 ($0.63) to BRL143.20, according to BCB data – which the new system will undercut.

In December 2018, BCB approved the requirements for the instant payments system, for which it will act as single settlement infrastructure operator. These requirements establish the system’s basic characteristics, including governance, forms of participation, centralised infrastructure settlement services, connectivity and liquidity provision.

In consultation with stakeholders, the BCB will define the instant payments ecosystem’s regulation. The system is expected to be flexible and open, to ensure access for and the emergence of participants offering innovative services meeting the needs of users, BCB says. The new instant payment system is designed to replace cash and speed up existing retail payment systems.

Currently, for purchases Brazilians use cards, cash or boleto bancário, a barcoded bank slip that can be settled at payment points such as convenience stores, supermarkets or bank branches. Accounting for around 25% of all online payment transactions, boleto bancário is popular both with enterprises and with consumers who lack credit cards or prefer the security of offline or cash payments.

In addition, for the 55 million unbanked Brazilians, boleto bancário is currently the only means of payment for goods or services purchased online.

Market overview

According to BCB, 86.5% of Brazilians aged over 15 had bank accounts in 2017, while 44% of adults had credit cards. Some 66% of total transactions took place via remote channels in 2017.

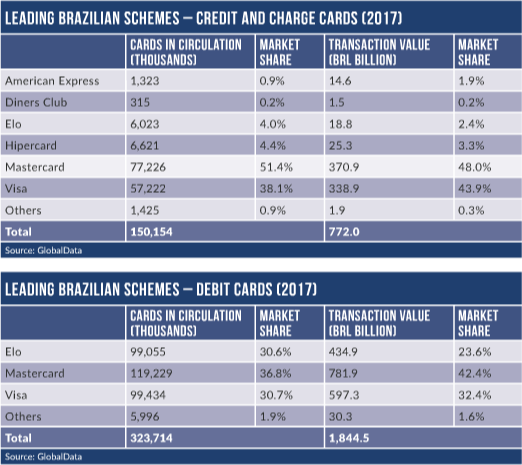

The Brazilian association of credit card and service companies, Associação Brasileira das Empresas de Cartões de Crédito e Serviços, says that in the third quarter of 2018, purchases with credit, debit and prepaid cards rose 14.7% year on year to BRL391.1bn. Credit card purchases rose by 14.8% to BRL244.4bn, debit cards by 13.7% to BRL143.8bn, and prepaid cards by 67% to BRL2.9bn. There were 606 million physical cards in circulation in Brazil at the end of 2017. As a large number of cards are combination cards, with both a debit and a credit function, the total number of card functions was therefore higher, at 741 million.

At the end of 2017, Mastercard, including Maestro, had 21% of the market, followed by Visa, including Visa Electron, with 20%. Elo, Brazil’s domestic card scheme, which competes with international brands, had 14%, while other domestic schemes had 10%. Amex had 0.2%, Diners Club 0.03%, and privatelabel cards 35%.

“Elo is big in debit, approaching 25% market share, and will likely overtake Visa as the second-largest brand in the first half of 2019,” says Guilherme Lima, CEO of Brazilian consultancy Ponto Futuro Consultoria Estratégica. “Its market development in credit cards has been more challenging.”

Lima continues: “Elo’s credit card market share is still below 5%, and its growth has only ramped up in since 2016, after ensuring international acceptance via Discover. Also, Elo still has to overcome a perception of narrower acceptance compared to Visa or Mastercard, and lower brand equity, which makes it harder for Elo to be consumers’ preferred card of choice.

“Contrary to debit, it’ll take a few years before Elo can challenge Visa’s credit card dominance position, even taking into account the big marketing push by Elo’s shareholders, Bradesco, Banco do Brasil and Caixa Econômica Federal.”

Lima explains that GPR prepaid cards never really took off in Brazil. “They are mostly confined to very specific niches, such as paying wages for domestic workers and other unbanked groups,” he says. “A key challenge that GPR program managers and specialised GPR issuers face is the lack of a cost-effective cash-out network, as the ATM market is dominated by large banks. They charge substantial fees to provide access to their ATMs.”

NFC/Contactless

Despite high levels of smartphone adoption in Brazil, NFC payments still have not become mainstream.

Lima notes that contactless card issuing has been negligible in Brazil, despite most POS terminals being contactless-ready. “Samsung Pay was launched in 2016 in Brazil, and Apple Pay in April 2018,” he says. “Apple Pay seems to have gained modest traction faster, having launched with a more distinct focus of its target public – affluent and mass affluent – and leveraging a partnership with an issuer, Itaú Unibanco, and merchant promotions.”

Google Pay launched in March 2019, in association with rival bank Bradesco.

In September 2018, Cielo, Brazil’s largest acquirer, launched a QR code-based mobile payment system with its two shareholders, Bradesco and Banco do Brasil, and other partners. Its QR Code Pay system aims to sign up 40 million users both for MPoS payments and e-commerce transactions.

In August 2018, Itaú Unibanco, Rede and PayPal announced a digital payments partnership to facilitate online and in-app purchases. PayPal Brazil’s general director, Paula Paschoal, told Reuters that the company expected to add one million users to its 3.8 million clients in Brazil in two years as a result of the partnership; as of August 2018, 300,000 merchants in Brazil used PayPal.

“The partnership is designed to make it easier for customers to link their Itaú credit cards – Itaú, Itaucard, Hipercard and Credicard brands – to their PayPal wallet,” an Itaú spokesperson tells EPI. “Also, the partnership will increase the security and authentication of transactions. Itaú, Rede and PayPal will work closely using data tools, risk analysis and anti-fraud systems to provide a secure, convenient shopping experience online and in-app.”

Customers’ linked Itaú cards can be specified by the customer as a payment option in their PayPal account.

Acquiring

In 2010, the government ended the monopoly under which only two acquirers were allowed to operate in Brazil, Visanet, now Cielo, and Redecard, now Rede.

It also ended the exclusive relationships that Cielo had for capturing Visa cards and Rede for Mastercardbranded cards.

In 2013, BCB introduced new regulations to ensure that merchants had freedom to choose which acquirer or processor they wanted to use. According to Brazilian consultancy Boanerges and Cia, there were at least 13 acquirers in Brazil in 2018.

Additionally, as of May 2018, there were 377 fintechs in Brazil, with 25% of them dedicated to payments and remittances, according to Finnovation.

Foreign investments

There is a growing trend for foreign investments in Brazilian fintechs.

Brazilian processor Stone Pagamentos raised $1.5bn in its Nasdaq IPO in October 2018, with Berkshire Hathaway and Ant Financial among its shareholders. PagSeguro raised $2.3bn in its IPO on the New York Stock Exchange earlier in 2018.

In October 2018, Visa made an unspecified investment in Brazilian digital payments processor Conductor. The two companies are collaborating to develop issuer-focused solutions for payments tokenisation via mobile wallets and to expand the use of push payments through Visa Direct. Also in October 2018, China’s Tencent invested $180m in Brazilian fintech Nubank, which plans to offer consumer loans in addition to its existing credit cards and digital payment accounts.

In February 2018, RecargaPay received $22m in Series B funding to roll out its mobile wallet and m-payment platform to unbanked and underbanked Brazilian consumers. Its mobile wallet is used by 10 million consumers, enabling them to pay bills, top up cellphones and buy public transit cards and gift cards.

“Brazil’s payments industry has attracted a lot of international interest and capital, examples being Stone’s and PagSeguro’s 2018 IPOs,” says Katie Llanos-Small, editor of Latin American financial news provider Iupana. “It’s a big market and there’s still a lot of potential for growth.”

There’s still a long way to go for contactless payments in Brazil. Roughly 80% of POS are NFC-enabled, but most are concentrated in the big cities.

Open Banking

Brazil’s Open Banking initiative has a very wide reach and includes a mandate covering banking product information as well as transaction and balance information and payment initiation.

Although Open Banking was initiated under Brazil’s previous government of President Michel Temer, the new government of President Jair Bolsonaro does not want to change the regulations being developed, notes Burelli.

Open Banking regulations are expected to be released in phases over a period of three years. The initiative aims to foster competition within a concentrated financial services industry that, while having many players, is concentrated in a small number of institutions holding majority market share in various products.

Llanos-Small says Brazil’s big banks are actively looking at how API platforms work, and how they can use APIs and benefit from them. “This has largely been a proactive move by banks, not one that’s really been pushed by regulators,” she says. “But it’s clear that Open Banking is going to be mandated in Brazil.”

While Itaú Unibanco had not developed Open Banking APIs as of November 2018, according to Itaú IT director Lineu Andrade, Iupana reports that Bradesco, Banco do Brasil and digital-only Banco Original are experimenting with open APIs. Banco do Brasil launched its Open Banking developer portal in June 2017.

“Although technology plays an important role in Itaú’s advancement, we’re currently not developing APIs for open payments,” said Andrade when interviewed in November 2018. “We seek to become a digital bank from the inside out, and invest in initiatives to improve the experience of our customers and employees. Technologies being adopted include the blockchain, the cloud, machine learning and AI, plus the full digitalisation of client interactions and back-office activities.”

Itaú Unibanco has established the Cubo Itaú incubator, which covers various industries including fintech; in November 2018 it had 10 fintechs as members. Andrade says that by November 2016, over 60 projects had been set up by Itaú and by Cubo’s resident startups. “One example is BLU365, formerly Kitado, a debt-renegotiation platform that helps Itaú leverage leads and digital relationships,” he adds.

Competition

Open Banking will generate greater competition in payments.

By 2021, Brazil will have implemented open payments, so that non-bank fintechs can register as payments providers. Via Open Banking, non-banks will be able to initiate payments through current accounts or e-money accounts.

Brazil’s four major banks have a monopoly on current accounts and retail payments. Cards are expensive for merchants to accept, as the average merchant service charge is 2%, and retailers receive their funds after 30 days. Some card schemes charge merchants up to 4%.

Brazil has a relatively high cost of card payment acceptance compared to other markets, a relatively high cost of retail and SME credit, and a paper-based instrument, boleto bancário, which is pervasively used across many merchant categories. These factors provide an attractive market for fintechs and large merchants alike to target the development of business models, reducing the direct and indirect costs of payments and of liquidity.

With Open Banking, retailers could register as payments providers and incentivise customers with rewards to use their own realtime payments systems. This would save them 2-4% in merchant charges, and ensure instant payment from customers.

“Brazil is a highly sophisticated, mature market for financial and retailing services, with a growing digital and electronic and mobile commerce industry, where I would expect change to be driven rapidly by large players, possibly retailers or large-volume billers looking to reduce their cost of payments and to improve their working capital,” Burelli says.

“Some fast movers – fintechs and banks alike – will likely move rapidly onto the opportunity, partnering with brands from other industries in search of large-scale access to consumers, or developing value-added solutions to consumers or retailers.

“Also, the expected roll-out of mobile payment services resulting from Open Banking in Brazil will potentially target the 55 million underserved Brazilians. This is 26% of the total 211 million inhabitants, based on World Bank data.”