The coronavirus crisis is a turning point for the payment industry. For BoE’s Christina Segal-Knowles, two challenges are key to the future of payments. Mohamed Dabo reports.

Clear, transparent regulatory expectations are critical to ensure that uncertain rules of the game don’t hold innovation back, she said.

“Changes in the way we pay and the challenges we’ve seen over the past several months pose two important and interrelated questions for central banks and regulators,” she said.

First, how do we ensure that we have legislative and supervisory frameworks in place to support development of safe private sector innovation that could respond to these challenges?

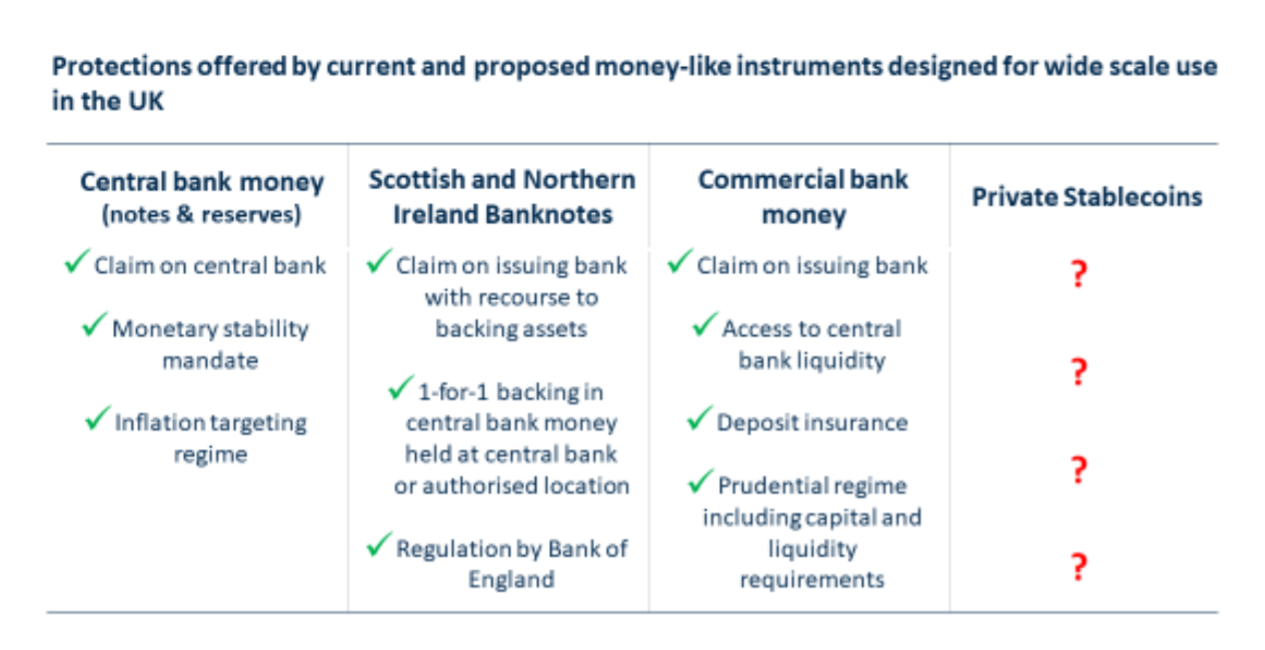

“Here, it is clear that we need to ensure that new ways to pay and new forms of electronic money offer equivalent protections to existing ones.”

And second, what is the right role for central banks in provision of the money we use to transact?

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataSegal-Knowles is executive director for Financial Markets Infrastructure (FMI) at the Bank of England.

She is responsible for supervising firms that enable payments for goods and services, record ownership of bonds and shares, and help financial market participants manage risk.

She also works on policy development related to these firms and the financial markets in which they operate.

Problem one

“Problem one for central banks is that robust and reliable ways to pay are essential to financial stability.”

The reliability and resilience of payments is so important to the economy that the UK Financial Policy Committee, tasked with identifying, monitoring and reducing systemic risks, lists avoiding serious interruptions in the provision of payment and settlement services as one of the very purposes of preserving financial stability.

If a stablecoins were to significantly replace current systemic payments chains as a way to pay – logic follows that they would pose the same risks to the economy as current payments chains and should be regulated to the same standards, she said.

“This is relatively straightforward: regulation should be technology neutral: based on the activity conducted and the risks posed, not the technology used or the entity’s legal form. In other words, same risks same regulation.”

“Where stablecoins are used in place of money, they need to offer the same protections as money.”

Source: Bank of England

Source: Bank of England

Problem two

Problem 2 is how do you ensure the stability of the “thing” being transferred in the payments chain. Existing systemic payment arrangements transfer money that is stable and reliable – in bad times and in good.

This generally takes two forms: public central bank money – either reserves held at the central bank or cash; or private commercial bank money – bank deposits.

Prudential regulation, access to central bank liquidity, and deposit insurance give holders confidence that underpins their willingness to receive commercial bank money as payment.

With the right regulation, stablecoins may be safe for use in systemic payments chains.

But the protections these stablecoins would offer are currently big question marks. Some major stablecoin proposals offer no legal claim for holders.

“If the shop can’t sell the stablecoin to get local currency or other goods in an amount equivalent to the price of the grocery order, tough luck.”

Additionally, many stablecoins propose backing in instruments that may have market and liquidity risk.

While these risks might be acceptable for speculative investment purposes, payments are different.

Stablecoins’ borderless nature also means that international regulators’ coordination is necessary and work is indeed underway.

Is there a role for central banks?

“The changes in how we pay have not just involved a switch from physical cash to electronic payment. It has also necessarily involved a switch from public, central-bank-issued money to private money.”

This is because central bank money is currently only available in physical banknotes or in reserves, which certain regulated financial institutions hold in accounts at the central bank.

For the public and most businesses, the only current option to hold money backed by the central bank is in the form of physical banknotes.

An alternative would be for central banks to issue a new electronic form of central bank money that can be used by households and businesses for payments, also known as a central bank digital currency or CBDC, she argued.

It also may be a safer alternative to new proposed forms of private electronic money like stablecoins, she added.

But a CBDC may also have significant implications for how our financial system works – in particular if households and businesses were to move their deposit balances from commercial banks to CBDC.

This could, in turn, affect how we implement monetary policy and support financial stability.