Two decades after 2,996 lives were lost in the 9/11 terror attacks, the wars launched in their names have claimed 900,000 more.

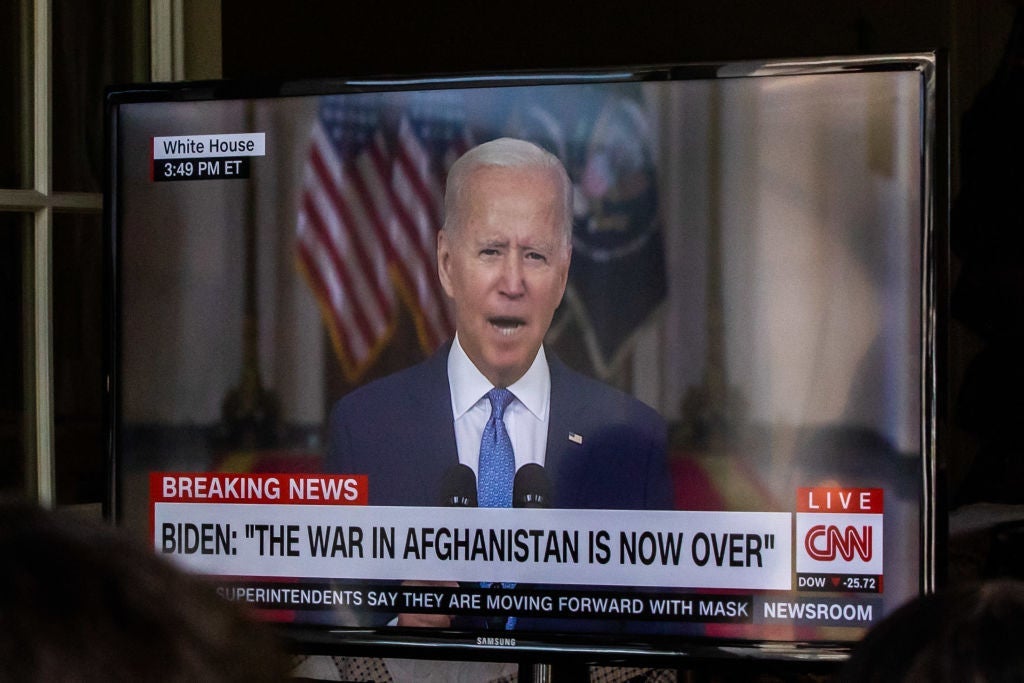

That is the conclusion of the latest report by Brown University’s Costs of War Project. The war in Afghanistan, launched within weeks of the 9/11 attacks and terminated in August by US President Joe Biden, is estimated to have killed 176,206 people – 96% of them Afghans, and more than one in four of them civilians (27%).

An estimated 5.9 million Afghans have been forced from their homes over the course of the war, representing 29% of the country’s pre-war population.

Spillover into neighbouring Pakistan is estimated to have claimed an additional 66,650 lives, including 24,291 civilians (36% of the total), while displacing a further 3.7 million people.

More destructive still, according to the report, was the 2003 invasion and subsequent occupation of Iraq.

Between 275,000 and 306,000 people are estimated to have died in the Iraq war, including between 185,000 and 209,000 civilians – 68% of all fatalities. The total fatalities represent between 1.1% and 1.2% of Iraq’s pre-war population, a burden comparable to that experienced by Italy in the Second World War. More than one in three of Iraq’s pre-war population have been displaced by the conflict (37%).

The total number killed in all the conflicts stemming from the War on Terror, estimated at between 897,000 and 929,000, is greater than the death toll of the US Civil War and approximately 300 times larger than the death toll of the 9/11 terror attacks.

That death toll stands in stark contrast to the deaths caused by Islamist terror attacks in Western Europe and North America since 9/11, which stands at 828, according to the Global Terrorism Database.

Criticism of Biden's decision

The figures add context to heated criticism of Biden’s decision to terminate the conflict. Many have called for the indefinite continuation of US involvement, citing the relatively low coalition military casualty figures of recent years.

The war may have become relatively painless for Western militaries, largely a result of an Obama-era strategy of retreating into the skies, but little had changed for Afghans by the time of Biden’s withdrawal.

According to UN figures, between 2009 and 2020 the annual civilian death toll fluctuated between a low of 2,412 (in 2009) and a high of 3,803 (in 2018). Between 2014 and 2020, the number never fell below 3,000.

The eight-trillion-dollar war

The war in Afghanistan has been a defeat unlike anything experienced by the US since Vietnam. In 2001, the US joined Afghanistan’s civil war on the side of the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance, then in control of large swathes of the country’s north-east. Two decades later, armed opposition to Taliban rule is confined to parts of a single valley outside the capital.

While the US was successful in toppling Iraq’s government, the country’s supposed weapons of mass destruction and ties to al-Qaeda never materialised. Much as in Afghanistan, the institutions built by the occupation were weak, sectarian and riddled with corruption. A disastrous civil war in 2006 paved the way for the emergence of ISIS in 2014.

The failures of each were not due to a lack of funding. According to the Costs of War Project, the total price tag of the post-9/11 wars (including interventions in Syria, Yemen and elsewhere) is $8trn – four times larger than Biden’s climate plan.

Much of this money has gone into the private sector. Since 2008, according to US government figures, federal contracts for operations in Afghanistan and Iraq have netted private sector actors $210bn – a sum that excludes war contracts for activities based in neighbouring countries, such as Pakistan, and defence procurement at home.

US aerospace giant KBR has been the biggest beneficiary of these contracts, securing deals worth at least $40bn over the past 13 years.

The budgetary cost of the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere have been only part of a decades-long increase in US defence spending. According to the World Bank, the past 20 years have seen annual US defence spending grow from $332bn to $723bn.

The Institute for Policy Studies recently estimated that, since 9/11, the US has spent $21trn on foreign and domestic militarisation, including $16trn in military spending and $949bn in spending on homeland security.

The report estimates that $7.2trn has gone into military contracts. An analysis by the Intercept recently found that the stock prices of the five largest US defence contractors have collectively outperformed the S&P500 by 58% since 2001.

As an article by Slate notes, the vastly expanded profits of these companies have not come primarily from the sale of arms, vehicles and mercenaries for use in Afghanistan or Iraq. Much more significant to their balance sheets has been renewed tensions with Russia and China, tensions which have led to an explosion of investment in nuclear weapons, missile defence systems, space-based systems, cyberwarfare infrastructure and the development of new ships and planes.

Far from drawing down these conflicts, Biden’s rationale for withdrawal from Afghanistan is that it will allow greater attention to be focused on the Asia-Pacific region.

Moreover, it now seems likely that US involvement in Afghanistan will not be ending entirely, but instead joining the ranks of the superpower’s covert drone wars – such as those waged in Somalia, Yemen and Libya.

The US defence sector, it appears, has little to worry about.