LinkedIn – the social media platform owned by Microsoft and used by professionals all over the world, to network, share ideas and find jobs – frequently conducts research to keep abreast of workplace trends, the interests of employers and the changing views of workers. One survey asks a straightforward question: “What are the most important and desirable skills that employees should possess?” Dynamic markets require a dizzying range of skills and smarts, so answers vary over time. Context matters, too. Certain jobs require skills that others have no use for. The ability to ensure that a balance sheet balances is a useful skill for financiers, but not so much for firefighters. Yet one skill appears ubiquitous to employers’ wish lists, regardless of the job or where in the world it is located.

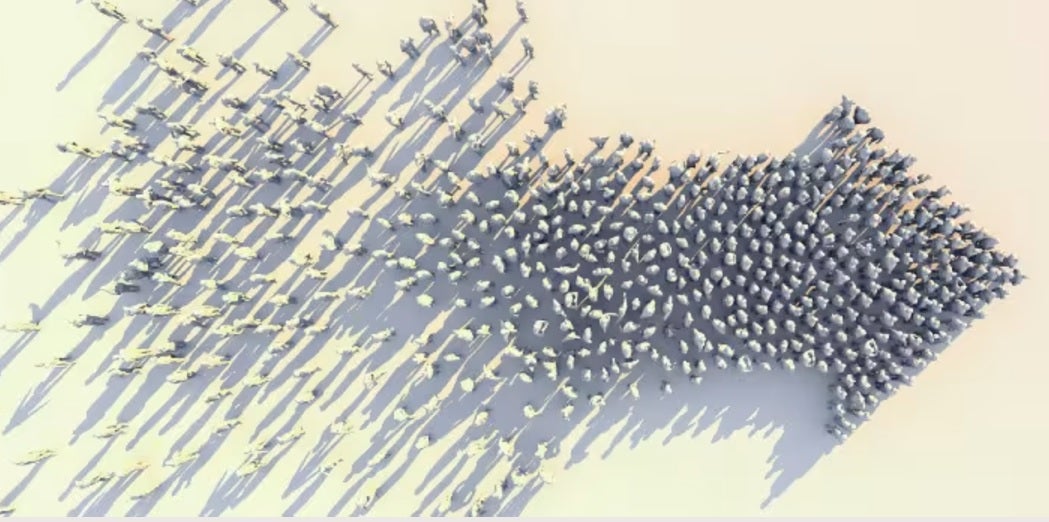

Surveys such as these illustrate the crucial role influence plays in the workplace. Without influence it’s hard to make progress and effect change. Influence can transform a routine idea or otherwise ignored appeal into a compelling vision that opens minds, transforms doubters and turns intentions into actions.

But influence is not straightforward or easy. Much of what we are taught about how to influence and persuade others sounds fine in theory but frequently differs in practice. Take, for example, that familiar organisational mantra that all decisions are made on the basis of the best evidence supported by a robust economic case. It’s a worthy aspiration, and it probably serves as a reassuring narrative, too. But most of us have experienced the frustration of having our proposals and appeals rejected even though they are founded on reliable facts and solid financials. When it comes to persuading others, having a good case to make is rarely enough. Why? Because having a good case to make is not the same as making your case well.

How do you make your case well? One way is to understand all the rules of influence and not just those dictated by logic, finance and company policy. Forty years ago Robert Cialdini published Influence – The Psychology of Persuasion, a book describing seven universal principles of influence that, beyond evidence and economic self-interest, reliably influence people to say ‘yes’ to requests. They are reciprocity, liking, unity, authority, social proof, commitment and consistency, and scarcity. Beyond facts and finance consider them reliable triggers to “yes”.

1. Reciprocity

After scoffing Happy Meals and playing with the other kids, children who make a weekend visit to one of McDonald’s fast-food restaurants in Bogota, Colombia know one final moment of joy awaits. At the exit, staff are on hand giving out red balloons – one per child.

The balloons are good for business. Happy kids mean happy parents. And happy parents return, boosting sales. So when we suggested a subtle change to this policy the managers’ reluctance to tinker with a winning formula was understandable. Putting their initial scepticism aside, however, they ran an experiment and immediately measured a 20% increase in sales… of coffee.

The change we suggested was simple. Rather than give the balloon when families leave, offer it on arrival. The reason this subtle, costless change made a big difference concerns reciprocity – people feel obliged to give back to others the form of service, gift or favour they have first received. A balloon given to a child on leaving serves as a reward for visiting. But a balloon given on entry is a gift. And as the societal rule mandates, if you give something to me then I should return the favour.

But why coffee – an item that children are unlikely to order? It’s because a gift given to a child is really a gift given to parents. It’s easy to see how an obligated parent may return that favour by buying themselves a cup of coffee. Over the next six months millions of dollars of extra coffee was sold.

A clear lesson emerges for anyone seeking to persuade others. Those who seek to give or help others first, will often find themselves benefitting from an audience ready to return the favour when they need assistance. If you want others to help you, then give help first. And if you want people to trust you, trust others first.

Importantly, reciprocity is not only fundamental to cooperation between individuals. It also plays an important role in the effectiveness and collaboration of teams, departments and organisations, too.

2. Liking

People prefer to say yes to the people they like. Although many factors contribute to liking, one, in particular, stands out. Commonalities.

Take negotiations. In one experiment, executives were tasked with negotiating on a large deal. Half were told that “time is money” and they should quickly get down to business. The other half were asked to spend a few moments prior to negotiating in an attempt to find commonalities and make a connection. This social investment proved worthwhile. Compared to the 30% who deadlocked in the “straight down to business” condition, only 6% who sought out commonalities before haggling stalemated. When the spoils of the negotiations were counted, those who identified prior commonalities also walked away with a much better deal for both parties.

Importantly, these experiments were conducted online. Post-pandemic, the widespread adoption of hybrid working results in many of our influence challenges playing out virtually. Studies like these provide a useful reminder that behind that screen of pixels is a human who is subject to exactly the same fundamental motivations to connect with others as we are. To disregard this point in exchange for haste and efficiency seems a fool’s errand.

3. Unity

When social psychologist Mark Levine arranged for fans of Manchester United to encounter someone who needed help (an injured runner) moments after discussing the love for their football team, they were much more likely to offer assistance if the unfortunate jogger’s shirt was the same colour as their team’s. And much less likely when it was a different colour. Mark’s experiments illustrate the power of shared identities and how requests made by those who share one increases the inclination to say yes. Not because they are like them, but because they are one of them.

Successful persuaders recognise the importance of unity and take steps to highlight those that genuinely exist. But what about situations where there is little in the way of existing unity, like a diverse workplace. The advice for leaders is to focus on two things. Firstly, frequent contact. To persuade others, you should be in the regular presence of others. Secondly, the synchronisation of ideas. Co-developing projects and proposals rather than producing them in isolation can help. So can seeking advice rather than feedback. When we ask for feedback we often get a critic. But asking for advice often results in us acquiring an accomplice who, consequently, is more likely to view themselves as united with us.

4. Authority

When people are uncertain, they look outside of themselves for guidance. One place they look is to credible, knowledgeable experts which makes the way we are introduced matter. A few years ago we demonstrated how much by arranging for a team of London-based estate agents to have their expertise and credentials be introduced prior to meeting potential clients. Immediately the firm measured a 20% increase in valuation appointments made and a 15% increase in contracts signed as a result.

During the pandemic, we showed how the idea can extend to online meetings. By including their qualifications (e.g. CFP, APFS) alongside their displayed name on Zoom and Teams calls, one firm of financial professionals reported an increase in follow-up appointments and referrals. Investing money with Robert Cranston FPC is, it seems, more reassuring than giving your cash to plain old Bob.

5. Social proof

Imagine you own a restaurant and want to persuade more customers to order a dessert to provide a welcome boost in sales. What do you do? Turns out that a costless and entirely ethical strategy is available to you. On your dessert menu write the following six words alongside your bestselling dessert: “This is our most popular dessert”.

Numerous studies have demonstrated how this honest alert can increase sales by as much as 18%. The reason concerns the principle of social proof. People frequently choose what to do by looking at the behaviours of others like them. Social proof messages are not limited to the promotion of desserts. Studies have shown how, after being informed of the actions of comparable others, people are more likely to reduce their energy consumption, pay their taxes and turn up on time to health appointments.

But there is one context where we urge caution. Many managers lament the regrettable frequency of unwanted behaviours such as late-starting meetings or tardy timesheet submission in the hope people realise the negative impact and change their behaviour. We find the opposite is more likely to occur. Why? Because lurking within that message is a much more damaging and potentially normalising one: “Look at how many people are doing this undesirable thing.”

6. Commitment and consistency

Most people encounter personal and interpersonal pressure to behave consistently with their values and commitments. Particularly those they make voluntary, place effort in and state publicly. For persuaders the key is to start small and build. When researchers posing as road traffic safety officials went door to door asking householders if they would place a large sign on the front of their property with the words “Drive carefully”, few agreed. But one area bucked the trend with homeowners significantly more likely to agree to this unappealing request. Why? The previous week, those homeowners had been asked to place a postcard in the window of their car signalling support for the campaign. This small, voluntary act served as an initial commitment. When later asked to support the campaign by allowing the installation of a much larger sign, they agreed because the bigger request was entirely consistent with their earlier, smaller commitment.

Three things should be uppermost in any influencer’s mind when seeking to turn initial commitments into longer lasting support. Firstly, they should be voluntary. Secondly, commitments should require the person being influenced to take action or invest effort. Thirdly, and most crucially, commitments should be made in view of others

7. Scarcity

All of us succumb to wanting more of what we can have less of. Learning that the availability of something is scarce often increases our desire for it. Think Beanie Babies™, Football collector cards and toilet tissue during lockdown.

There are several reasons why scarcity of an item or opportunity, real or rumoured, drives people to want it more. An important one is our near universal aversion to loss. There’s a common saying in the financial services industry that is as entertaining as it is instructive. “Phone a client at 4am and tell them if they act now, they’ll make twenty grand; the client will fire you. But phone a client at 4am and tell them if they fail to act now, they’ll lose twenty grand; you’ll have a customer for life.”

Notice in this scenario that the client and the money are the same. The only thing that changes is whether attention focuses on the gain or on the loss.

The implications for influencers and communicators is clear. If your proposal or proposition has a feature or attribute that is genuinely unique or scarce, then ensure it is made prominent to your audience and, where appropriate, point out what they may stand to lose if they fail to consider your offer.